💥Keep Your Equity: Non‑Dilutive Funding for Startups

Synthesizing Insights From the Data

👋 Hi, I’m Andre and welcome to my newsletter Data Driven VC which is all about becoming a better investor with Data & AI. Join 34,515 thought leaders from VCs like a16z, Accel, Index, Sequoia, and more to understand how startup investing becomes more data-driven, why it matters, and what it means for you.

ICYMI, check out our most read episodes:

Brought to you by Harmonic — The Complete Startup Database

Market maps finally work in venture software. Scout — the AI agent made for VCs allows you market map with ease. Simply describe what you’re looking for, or look up the competitive landscape for a particular company.

Scout handles the rest, scouring the internet as well as Harmonic’s private database trusted by thousands of investors from leading firms like GV and Insight.

Equity vs Non-Dilutive Funding

Early-stage founders often default to raising venture capital, but giving away a slice of your company isn’t the only way to fund growth with external capital.

In today’s market, more founders are exploring non-dilutive financing – capital that doesn’t require selling equity – to extend their runway while retaining full ownership.

From revenue-based financing and venture debt to government grants, these options can be powerful tools if used wisely. Today’s deep dive compares key non-dilutive funding options for pre-seed to Series A startups (especially in tech/SaaS), and weighs their real costs versus traditional VC funding.

Let’s dive in! 👇

The Non-Dilutive Funding Toolkit

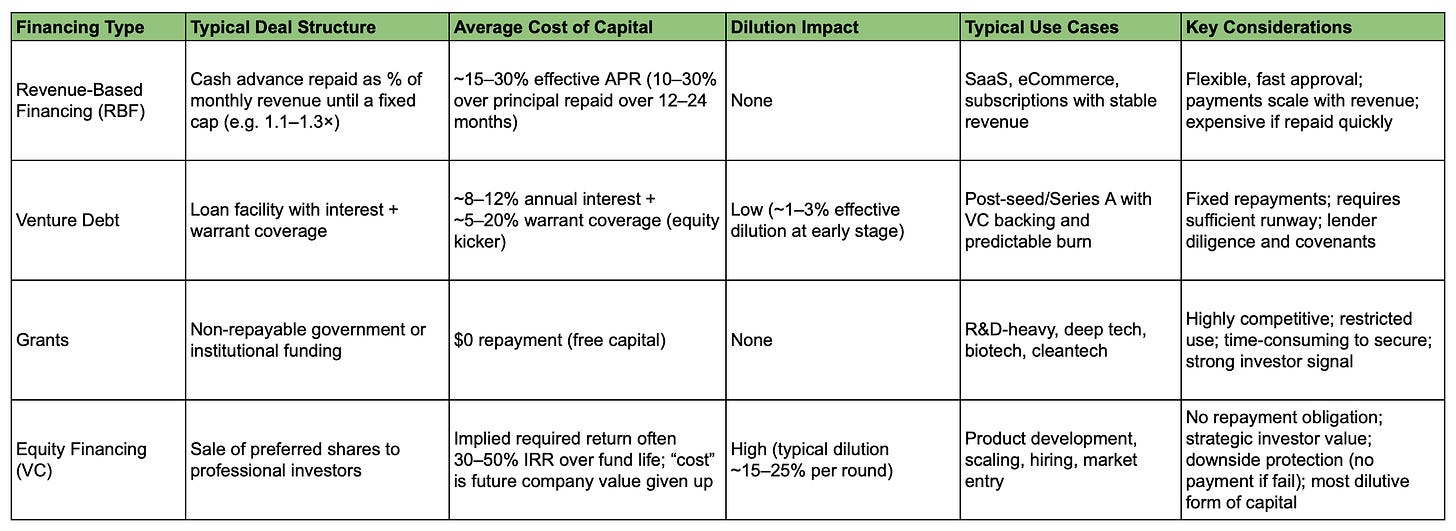

Revenue-Based Financing (RBF): Basically “Cash Now, Pay as You Grow“. RBF provides upfront capital to startups in exchange for a percentage of future revenues (often until a fixed payback amount is reached). It’s like selling a share of your future income instead of your company’s equity. This has become popular with SaaS and subscription businesses that have predictable recurring revenue (a16z, 2025).

Platforms like Pipe, Capchase, and Clearco can advance cash (sometimes within 24 hours) based on your monthly recurring revenue (a16z, 2025). For example, a startup might sell $5 million of future monthly revenues for $4.5 million today, getting cash now and repaying over time from revenue (a16z, 2025). The big appeal: It’s fast, requires no personal collateral or lengthy diligence, and doesn’t dilute your cap table (a16z, 2025).

However, the convenience comes at a cost. RBF providers charge a flat fee or take a revenue cut that often equates to a high effective interest rate. For instance, a 10% fee on an advance repaid over 12 months actually works out closer to a 20% annualized cost of capital (since you’re paying it back as revenue comes in) (a16z, 2025). In other words, RBF can be more expensive than bank loans, but potentially cheaper than giving up a huge equity stake if your company’s value skyrockets later.

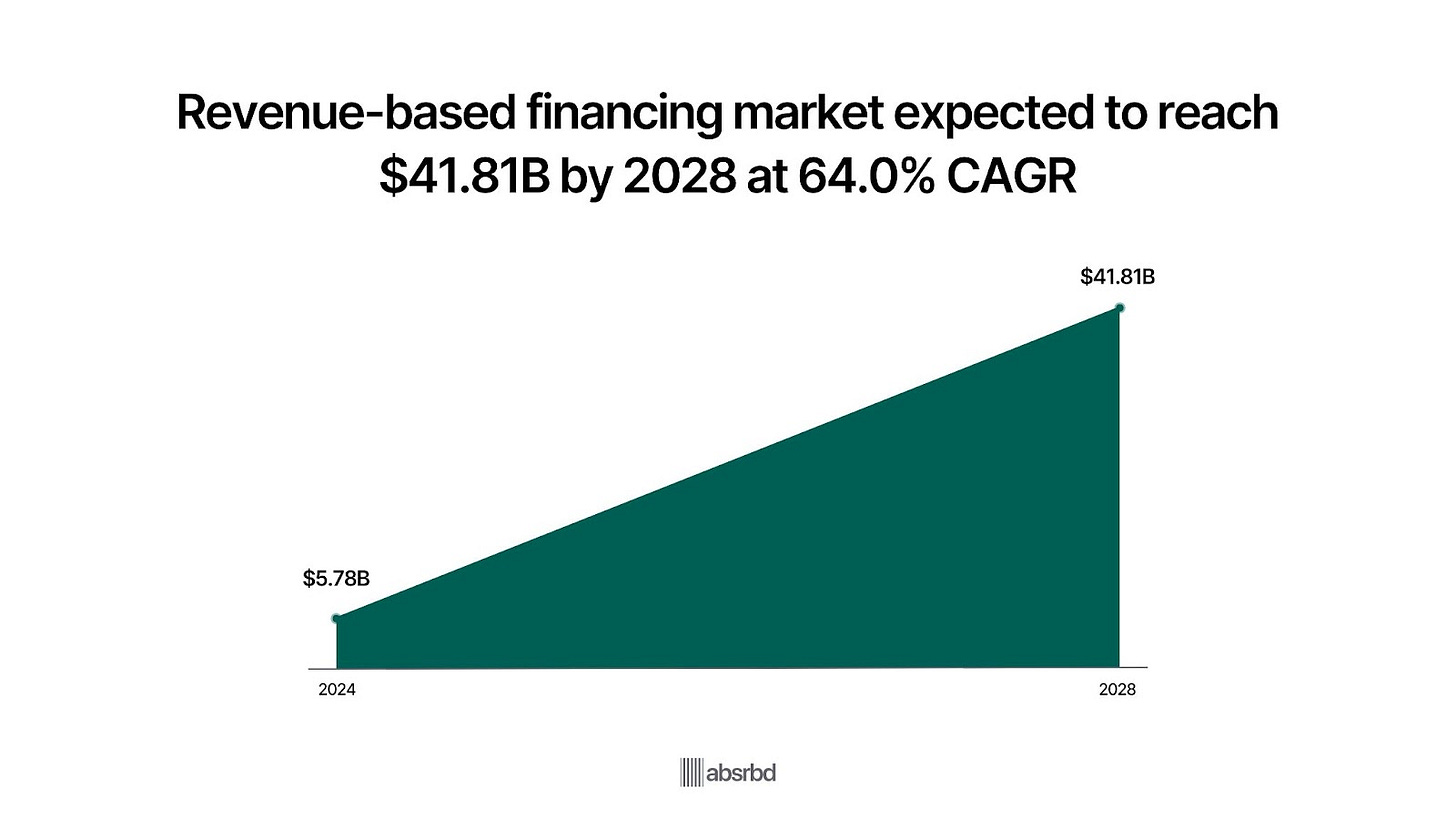

The RBF market is still relatively small (around $5.8 B in funding in 2024, globally), but it’s growing at an explosive ~70% annual rate as more founders learn about this option (absrbd, 2025). It’s best suited for startups with at least several months of revenue history and healthy gross margins – think of it as fuel for scaling marketing or inventory when you’re confident those dollars will generate future revenue to repay the advance.

Venture Debt: Loans with a Startup Twist. Venture debt refers to loans from banks or specialty lenders that are designed for venture-backed startups. Unlike a traditional bank loan, venture debt usually doesn’t require hard assets as collateral; Instead, lenders rely on your VC investors’ backing, your revenue traction, or both.

These loans typically charge interest (often a few percentage points above the prime rate) and may include a warrant, i.e., the lender gets the right to buy a small amount of equity at a nominal price. That warrant is the “equity kicker” that makes venture debt economics work for lenders.

For the startup, venture debt can dramatically lower the average cost of capital when combined with equity. VC Tomasz Tunguz gives a vivid example: Suppose a company raises a $5 M Series A round and sells 25% of the company to equity investors, then adds a $2 M venture debt facility. The equity cost ~25% dilution, whereas the $2 M loan might come with perhaps 5–20% warrant coverage (say 10% of the loan amount) – only about ~2% additional dilution (Tunguz, 2016).

In exchange, the startup gets extra runway. If that $2 M debt helps the company hit key milestones (e.g., doubling revenue in 5–6 months), the next equity raise could be at twice the valuation, meaning far less dilution in the future. In short, venture debt lets you delay the next dilutive fundraise, ideally until you can justify a higher valuation (SVB, 2025).

It’s no surprise that many startups have turned to debt: Venture lending grew rapidly in the 2010s (up ~16× over six years) and even surpassed Series A and B equity funding in dollar volume by 2016 (SVB, 2025). In 2024, U.S. venture debt issuance hit record levels (over $50 B, nearly double the 2023 amount) as startups looked to extend their runway without raising down rounds (Statista, 2025).

Venture debt is often used right after an equity round (e.g., a few months post-seed or Series A) to top up the cash balance. Lenders typically expect you to have 12–18 months of runway after taking the loan – they don’t want to be financing a last gasp (NVCA, 2023). Your startup should have fairly stable revenue or proven product metrics to qualify. Taking on debt when you’re burning cash with no clear path to repay is a red flag (and most reputable lenders will shy away from that scenario) (NVCA, 2023).

Also, remember: Debt must be repaid. If your business falters and can’t make payments, lenders may have legal rights over your assets or IP. In extreme cases, a default on venture debt can even result in the lender taking control of the business (SVB, 2025). That’s a key trade-off: Unlike equity investors, a bank wants its money back regardless of your startup’s outcome. Used judiciously, venture debt is a powerful tool to extend runway with minimal dilution, especially for SaaS startups with predictable subscriptions and for companies on the cusp of a big milestone.

Grants and “Free Money”: Fueling R&D without Dilution. Every founder’s dream is free capital that doesn’t cost equity or interest – that’s essentially what grants offer. Governments (and some foundations) provide grants to startups working on innovations in areas like science, medicine, defense, or clean energy.

The U.S. Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, for example, is the world’s largest source of non-dilutive funding for startups (GeekWire, 2024). SBIR and sister STTR grants have funneled over $1.6 B to startups in just Washington state alone over the years (GeekWire, 2024), and many famous tech companies (even a biotech unicorn like Seagen) got early SBIR grants (GeekWire, 2024). An SBIR grant typically provides ~$150K–$300K for a Phase I (proof of concept) and ~$1 M–$2 M for Phase II (prototyping, trials) (GeekWire, 2024).

In Europe, programs like Horizon Europe and national innovation grants play a similar role for non-dilutive tech funding. Startupticker (2025) has a useful list of European grants. The obvious upside of grants: no dilution and no repayment – it’s essentially non-recurring revenue to fund development. Grants can be transformational for deep-tech and hardware startups that need significant R&D before revenue. They also signal validation to investors; VCs generally view grant funding as a positive de-risking factor rather than “cheap” money (GeekWire, 2024).

The downsides: Grants take a lot of time and effort (writing lengthy proposals, navigating bureaucratic requirements, waiting months for decisions). They often come with strings attached on how you spend the money (specific research aims, reporting obligations, etc.) (MIT, 2025). And you typically can’t rely on grants for repeatable, fast funding – they are competitive (only a fraction of applicants win) and tied to specific projects. Still, for early-stage startups (especially in science-heavy fields), pursuing grants and R&D tax credits is a no-brainer to extend runway without dilution.

Other Non-Dilutive Options: Bootstrapping (reinvesting your revenues) is the original non-dilutive funding method – it forces discipline but means slower growth. Many founders now bootstrap to $1M+ ARR or profitability before considering VC, to avoid the “venture hamster wheel” altogether (Poyar, 2025). Big corporations or NGOs also run grant-like programs or innovation prizes in some sectors. There’s also crowdfunding: platforms like Kickstarter let you pre-sell products to raise cash (essentially revenue-based funding from customers), and equity crowdfunding can bring in investors without institutional VC (though selling equity to the crowd is dilutive, just not via VCs). Each alternative has its niche, but our focus here is on the three major ways (RBF, debt, and grants), which can substantially impact a startup’s financing strategy.

✈️ KEY INSIGHTS

Revenue-based financing offers fast, non-dilutive capital tied to future revenues but can carry effective annual costs of ~20%, with a ~$5.8 B global market growing ~70% yearly. Venture debt complements equity rounds to extend runway with minimal dilution (e.g., ~2% from warrants on $2 M debt) but must be repaid even in downturns, with 2024 U.S. issuance surpassing $50 B. Grants deliver non-repayable funding for R&D but require time-consuming applications and impose spending conditions, making them best for early-stage science-heavy startups.

Cutaway: The Rise of Seed Strapping

A growing number of early-stage founders are embracing “seed strapping”: A hybrid approach that combines small, strategic equity raises with disciplined bootstrapping and non-dilutive capital. Unlike classic bootstrapping (no outside money) or full-on VC (successive rounds at high dilution), seed strapping aims to minimize dilution while securing just enough external funding to hit key milestones (VC Corner, 2025). This trend is well reflected in an analysis by Carta, showing an ever-decreasing number of companies graduating from Seed to Series A (Carta, 2024).

Typically, a founder might raise a modest pre-seed or seed round (say $250K–$1M), often from angels or micro-VCs willing to accept founder-friendly terms. This money covers essential hires or product development. Simultaneously, they leverage revenue-based financing or small venture debt facilities to fund working capital and sales growth once there’s early revenue (GoHub Ventures, 2024). Grants or R&D credits further offset costs.

The goal is to extend runway and increase valuation before the next big round, reducing dilution when (or crucially if at all) a traditional VC raise happens. More SaaS founders are deliberately avoiding the classic “raise big or die” model, instead choosing “capital-efficient growth” that preserves founder ownership and optionality (GoHub Ventures, 2024).

Seed strapping is especially popular in markets where valuations have compressed, making large early rounds more dilutive than before (Carta, 2024). It’s also well-suited to SaaS and tech-enabled services with predictable revenue growth and strong gross margins. But it requires discipline: Founders need to manage cash carefully, line up multiple funding sources, and avoid over-leveraging with debt.

✈️ KEY INSIGHTS

Seed strapping isn’t just a compromise between bootstrapping and VC — it’s an intentional strategy to keep more of the company, stay flexible, and grow on founder-friendly terms.

The True Cost: Non-Dilutive vs. Equity Funding

The old adage goes: “Equity is the most expensive form of capital” . Why? Because when you sell a piece of your company, you’re not just giving up current value – you’re giving up a chunk of all future value, potentially a much larger amount. Let’s say you could raise $1 M by selling 20% of your startup to VCs, or instead take a $1 M loan with, say, a 10% annual interest. If your company grows to be worth $100 M, that 20% equity will cost you $20 M in ownership value (minus the VC’s share), whereas the $1 M loan costs you perhaps ~$1.1 M in total repayment. That’s the stark difference. Of course, if the company fails, the loan still needs to be paid (or the company goes bankrupt), whereas equity investors bear the loss – so equity is “cheaper” in a downside scenario. Founders need to balance these outcomes.

Venture Capital (Equity) – high upside cost, no required payback: Early-stage equity rounds often do seem expensive in dilution terms. Median dilution is around 20% at both seed and Series A in recent years , meaning founders typically give up a fifth of the company in each of those rounds. Do that repeatedly and you might own less than half your company by Series B or C. (In fact, Carta data shows that raising Seed through Series D at median dilution levels leaves founders with only ~40% of the company by the end.) The flip side: equity investors’ returns are entirely dependent on your success. They don’t get anything back until an exit, and if you stumble, you owe them nothing. This aligns incentives – VCs will cheer you on to grow the pie (often offering advice and network introductions as part of their “value add”), but they also expect a big multiplier (e.g. they might underwrite the investment, hoping for 10x return). That implicit return expectation is why giving up equity is so “expensive” – you’re trading a big chunk of your future for cash today.

Revenue Financing – known cost, but potentially high APR: In revenue-based financing, you do know the total dollar cost upfront (e.g., you’ll pay back 1.2× the amount advanced, as a percentage of revenue over, say, 12–24 months). This certainty and flexibility (pay more when revenue is high, less when low) is an advantage (GetVantage, 2024). However, as noted, the effective interest rate can be steep, often in the 20–30% annual range for fast payback deals (a16z, 2025). If your startup has sky-high growth (and thus could attract great VC terms), RBF might actually be pricier than equity in the short run.

But if you plan to grow steadily without seeking a unicorn valuation, paying a 20% fee on a one-time advance could be far cheaper than giving away 20% of your company. The key is your expected trajectory: RBF is a bet that your future revenues will materialize to pay it off, and that by avoiding dilution, your existing shares will be worth much more later. Many founders use RBF tactically – e.g., to fund a marketing campaign or bridge a seasonal cash gap – rather than as a primary source of funding for multiple years.

Remember that, unlike a VC, an RBF provider doesn’t take equity or a seat at your table; on the plus side, that means no loss of control, but on the minus side, you don’t get any mentorship or network from them (and platforms essentially remain one step removed (a16z, 2025).

Venture Debt – low dilution, moderate interest, strict terms: Venture debt’s cost of capital is usually much lower than the “cost” of equity. Interest rates might be on the order of 8–12% annually (this varies with market rates), and warrants might add a couple of percent dilution. As the Tunguz example showed, $2 M of venture debt might only dilute ~2% of equity via warrants, versus, say, 10–20× that dilution if you raised the same $2 M as equity (Tunguz, 2016).

In a successful scenario, that difference is massive – founders keep much more ownership. However, debt has fixed obligations. You’ll be making monthly payments of interest (often interest-only for a year or two, then principal amortization kicks in). Failing to meet those can put your company in jeopardy. There’s also usually covenants: For instance, a requirement to maintain a certain amount of cash or a limit on further debt. These terms are negotiable, but lenders will enforce them to manage risk. The effective “cost” of venture debt isn’t just the interest—it’s also the loss of flexibility. If your business hits a rough patch, you can’t simply tell the bank, “sorry, no growth this quarter.” You still owe the payments.

That rigidity is why venture debt is best used when you have a clear plan (and ability) to repay – e.g. using it to boost growth when metrics are strong, rather than to survive when metrics are weak . Many startups treat venture debt as an insurance policy or extension after an equity round: it’s there if needed, but if business goes great, you might even refinance or pay it off early.

One more consideration: taking on debt can sometimes make equity investors nervous (debt sits senior to equity in a liquidation scenario). Top-tier VCs are generally comfortable with a reasonable amount of venture debt, especially if it extends runway to hit milestones. In fact, some VCs actively encourage portfolio companies to use debt to minimize dilution (SVB, 2025). But if you’re loading up on debt when your prospects are shaky, new investors in a future round might see that as a sign of desperation.

Grants – no financial cost, high effort, strategic value: A pure grant doesn’t require payback or equity, so in monetary terms it’s free. The “cost” is in the effort and time to get it (and sometimes the slower pace of progress if you rely on grant funding). Founders of deep tech startups often patch together multiple grants to avoid fundraising too early – effectively using government money to reach technical proof-points.

This can pay off hugely: you retain full equity through those risky early stages and can raise VC later at a higher valuation once the tech is validated. Additionally, grants can be seen as a non-dilutive way to de-risk a startup’s story. Investors often ask “have you gotten any grants or awards?” as a credibility signal, especially in sectors like biotech, energy, or AI research.

The main drawback is that grants are not assured or repeatable – you might spend 3 months on an application and end up with nothing. And even if you win, grant funds can take time to arrive and are usually earmarked for specific uses. Thus, while the dollar cost is zero, the opportunity cost can be high if grant hunting distracts from building the business. A good strategy is to pursue grants in parallel with other funding efforts, not as a last resort.

✈️ KEY INSIGHTS

Equity funding is the most expensive long-term option, trading 20%+ dilution per round for no repayment obligations and investor alignment, with founders often ending Series D owning ~40%. Revenue-based financing offers predictable but high effective costs (20–30% APR), best for tactical uses when growth is steady but can be pricier than equity if valuations soar. Venture debt delivers low dilution (~2% via warrants) at moderate interest (8–12%) but requires strict repayment discipline, while grants cost no equity or cash but demand significant time, with funds tied to specific R&D goals.

When (and When Not) to Use Non-Dilutive Financing

Choosing the right financing tool comes down to your startup’s situation and goals. Here are some scenarios where non-dilutive options shine for early-stage founders:

You have revenue (or contracts) and want to scale faster. If you’re generating revenue – say a SaaS startup with $50k MRR – and you see an opportunity to pour gas on the fire (e.g., spend on customer acquisition) without waiting for the next equity round, RBF can be ideal. It’s available on-demand and quickly when you meet the criteria (many RBF firms require ~$500k ARR and a few months of stable revenue) (a16z, 2025). By using future revenue to fund today’s growth, you can accelerate between equity rounds. Best for: SaaS, ecommerce, or subscription startups with strong unit economics. Caution: ensure the repayment rate (often a fixed % of monthly revenue) won’t starve your operating cash. If your growth stalls, RBF payments still come first out of revenue, which can pinch your cash flow, so don’t over-leverage your future revenues.

You just raised an equity round and want extra runway. Venture debt is commonly used within 1–2 quarters after a Seed or Series A raise. At that point, you have fresh investor backing (which lenders like to see) and a plan for the next 12–18 months. Taking, say, a 20–30% additional cushion in debt can let you hire those few extra engineers or extend your runway from 18 to 24 months, giving you time to hit bigger milestones before the next fundraise. Best for: Post-seed or Series A companies with a clear growth plan and burn under control. This is especially popular in capital-intensive tech (hardware, biotech) or steady-growth SaaS, where hitting $X million ARR will significantly boost the Series B valuation.

Caution: Don’t use venture debt to “bridge to nowhere,” i.e. to avoid an inevitable down-round without a plan for achieving the metrics needed for an up-round (NVCA, 2023). If you’re almost out of cash and take on debt just hoping something good happens, you’re setting up for a crash. Also, when considering debt, start conversations early – as J.P. Morgan’s startup banking arm advises, engage when you have 12+ months runway, not when you’re desperate (NVCA, 2023).

Your work is R&D-heavy or aligns with grant programs. If you’re building deep technology (AI research, new battery chemistry, novel medical device) or anything that governments love to fund, go for grants early. Non-dilutive awards can fund your proof-of-concept, after which raising VC will be much easier (and you’ll command a higher valuation). Early grant funding essentially increases your negotiating power with investors by reducing technical risk on someone else’s dime (GeekWire, 2024). Best for: Deep tech, healthcare, cleantech, and academic spinouts. Also, certain geographies – for instance, the EU has generous SME grants, and various U.S. state programs offer seed grants – so look locally too.

Caution: Plan your runway with grant timing in mind. If a grant application takes 6 months, you might not see cash for a year. You may need bridge funding (perhaps a small SAFE note or an RBF advance) to keep going in the meantime. Also, be mindful of grant conditions – some grants restrict using funds for certain expenses or require you to share IP or publish results (e.g., EU Horizon grants expect open dissemination in some cases). Make sure those conditions don’t conflict with your business strategy.

You want to avoid the VC treadmill (at least for now). Not every great business is VC-scale, and even those that are might benefit from delaying VC reliance. As investor/advisor Kyle Poyar observed, many founders are now bootstrapping to $1–2M ARR or taking only a small pre-seed and reaching profitability, precisely so they don’t get forced onto the IPO-or-bust ride too early (Poyar, 2025).

Non-dilutive funding plays a big role for these founders: they might use RBF or small loans to smooth out growth, but fundamentally, they’re trading a bit of short-term cost for long-term control. If you relate to this, map out a plan to reach sustainability through revenues plus non-dilutive boosts. It might take longer to grow, but you’ll own more of the company if and when you eventually decide to raise larger funding. In the words of one SaaS expert, this approach is like focusing on “solid singles and doubles” instead of swinging for homeruns – building a real business with less stress and dilution (Poyar, 2025). Best for: Founders who value control and have a clear path to profitability, or businesses in niches VCs ignore but with decent revenue potential.

Caution: Going it alone means you might lack the network or mentorship that experienced investors can bring. Consider building an advisory board or peer network to get some of that external insight.

When to stick to equity: Non-dilutive doesn’t always trump dilutive. If your startup truly needs rapid scale, huge capital, or if you’re pre-revenue with nothing to leverage for debt/RBF, then venture equity is likely the appropriate choice. Also, if having marquee investors on your cap table will significantly boost your credibility (say, in enterprise sales or hiring), the “strategic value” of VC money can outweigh the dilutive cost.

Equity funding is also more resilient in the face of uncertainty – you won’t have looming payments due if the economy or your sales cycle turns south. In many cases, a blend is ideal: raise enough equity to fund core product development and give you breathing room, and layer in non-dilutive capital for specific expansion projects or as an emergency reserve. For example, a hardware startup might use equity for R&D and manufacturing setup, venture debt for purchasing inventory, and grants for cutting-edge research partnerships – each funding source matched to the right use.

✈️ KEY INSIGHTS

Non-dilutive financing suits startups with revenue aiming to scale quickly (e.g., SaaS with $50k MRR) via RBF, but repayment obligations can strain cash flow if growth slows. Venture debt works best just after equity rounds to add 20–30% extra runway with minimal dilution, provided there’s a clear growth plan and enough runway to avoid desperation borrowing. Grants are ideal for R&D-heavy projects, delivering non-repayable funding that improves investor leverage, but require long lead times and compliance with spending restrictions.

So What?

1. Calculate the cost of each dollar. Before jumping into any funding, model out the true cost of that capital. If you take an RBF advance, what will you repay over the next year and how does that compare to what that amount of equity could be worth in the long run? Similarly, understand the dilution math of equity rounds – giving up 20% at a low valuation can be far more “expensive” than paying a 10% loan interest (MIT, 2025, Tunguz, 2016). Having a clear cost of capital comparison will help you decide the mix that maximizes your outcome.

2. Align the funding type with its purpose. Use non-dilutive funds for uses that will generate returns or unlock milestones in the near-to-mid term. For example, use venture debt or RBF to finance working capital, marketing, or a bridge to a known milestone (new ARR, product launch) – something that increases enterprise value before the next equity raise (SVB, 2025). Use equity funding for long-term bets and foundational development that may not generate immediate revenue (e.g., major product development, hiring key engineers). And use grants for what they’re intended: research, innovation, and public-good projects that also move your tech forward.

3. Ensure you can meet obligations. Non-dilutive isn’t “free” – failing to repay a loan or advance can kill your startup faster than a tight cap table would. So if you take on debt or revenue-based financing, bake the repayments into your budget with conservative revenue forecasts. Maintain the lender’s required runway and covenants (NVCA, 2023). Essentially, don’t bet your company on optimistic projections when using debt. If instead you realize you can’t safely service a loan, that’s a signal to either raise equity (accept the dilution as a trade for risk-sharing) or cut burn and extend runway organically.

4. Leverage “free money” aggressively (but wisely). If grant money or tax credits are on the table, go after them. These can meaningfully extend your runway with zero dilution. Just be mindful of the time investment: assign someone (a co-founder or hire a grant consultant) to own this process so it doesn’t distract the whole team. Also, consider the strategic value: a grant that forces you down a specific R&D path or a long-term commitment might not be worth it. But in most cases, non-dilutive capital sources like grants, competitions, or R&D rebates should be part of your funding strategy from day one. They can only strengthen your position when you do approach VCs later (GeekWire, 2024).

5. Seek strategic partners, not just money. Whether you go dilutive or non-dilutive, remember that capital is a means to an end. If you take VC money, look for investors who truly add value beyond the check – e.g. industry expertise, hiring help, introductions – to justify the equity you’re giving up (Rachitski, 2023). If you take venture debt, build a relationship with a lender who understands your business and will be supportive (some banks and venture debt funds can be great allies, whereas others are purely transactional). And if you’re using alternative financiers (RBF platforms, etc.), supplement that with mentors or advisors who can fill the “smart money” role. In a nutshell: construct a financing strategy that doesn’t just fund your startup, but also sets you up with the right support and flexibility to execute your vision.

Thanks to Jérôme Jaggi for his help with this post.

Stay driven,

Andre

Thank you for reading this episode. If you enjoyed it, leave a like or comment, and share it with your friends. If you don’t like it, you can always update your preferences to reduce the frequency and focus on your preferred DDVC formats. Subscribe below and follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter to never miss data-driven VC updates again.

This is the clearest breakdown I’ve seen of how to actually use non-dilutive funding as strategic leverage rather than just ‘free money’.