👋 Hi, I’m Andre and welcome to my weekly newsletter, Data-driven VC. Every Thursday I cover hands-on insights into data-driven innovation in venture capital and connect the dots between the latest research, reviews of novel tools and datasets, deep dives into various VC tech stacks, interviews with experts and the implications for all stakeholders. Follow along to understand how data-driven approaches change the game, why it matters, and what it means for you.

Current subscribers: 2,087, +181 since last week

We’ve crossed the 2k subscriber mark within less than two months, thank you all! Today we’ll explore different ways of cutting through the noise and see how modern VCs find the needle in the haystack. But let’s start with a more fundamental question:

What makes a VC successful?

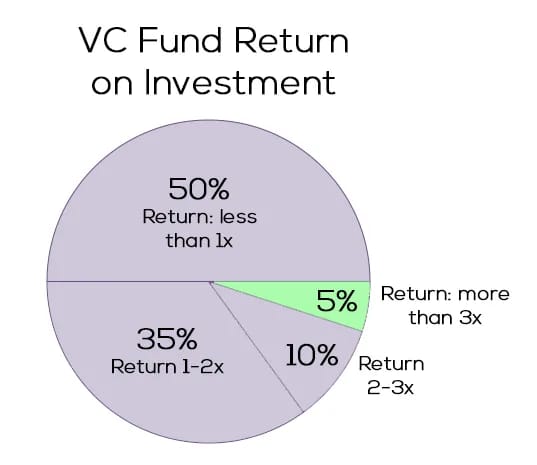

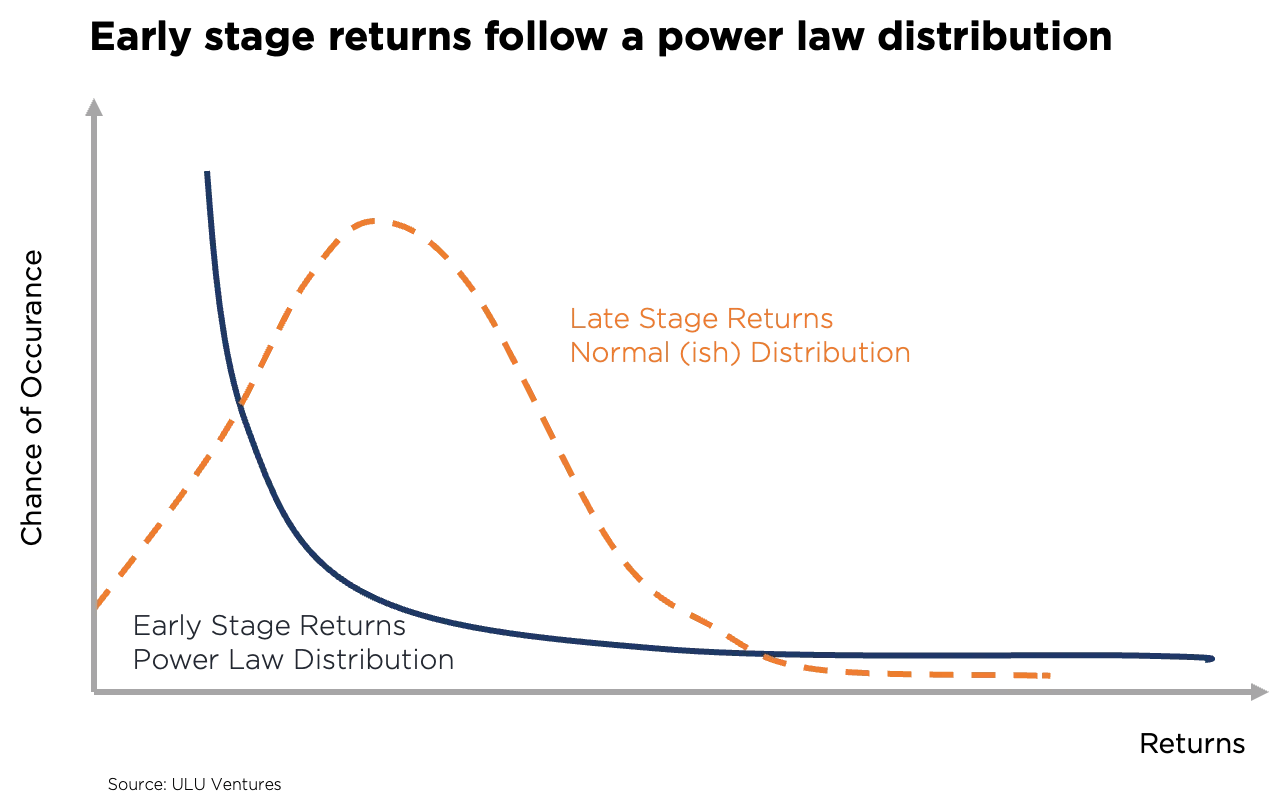

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” also holds true for “VC success”. Although we have been observing a shift from a pure financial return perspective to a more holistic ESG-centered one, the majority of GPs still operate with return on investment (ROI) top of their minds. On a portfolio level, early-stage VC returns are distributed based on a Power-law, whereas later-stage and private equity (PE) returns follow a normal distribution. In line with the most well-known Power-law distribution, the Pareto Principle (or “80-20-rule”), early-stage VC returns are driven by a high alpha coefficient that leads to oftentimes only 10% or less of the portfolio delivering 90%+ of the returns.

VC fund return distribution according to TechCrunch

Consequently, a well-performing early-stage VC fund with a portfolio of 25-35 startups depends on one or two outlier IPOs or trade sales and is comparably insensitive to write-offs. Said differently, early-stage VCs are upside-oriented #optimistbynature, whereas growth VCs and PEs rather try to limit their downside. In turn, every VC investment needs to have the potential to become one of the few outliers. I shared my thoughts and a rule of thumb on how big your startup needs to become to be a VC investment case here.

Return distributions of early-stage VC (Power-law) versus late-stage VC (Normal)

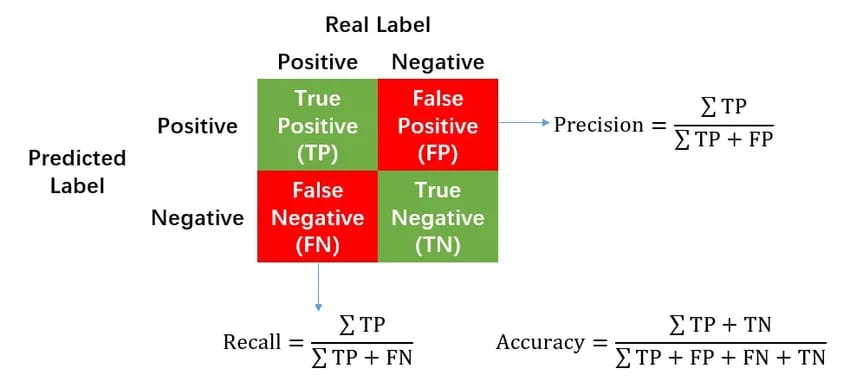

While early-stage VCs can afford to write off a significant portion of their portfolio, they cannot afford to miss an outlier. Translated into data speech: VCs face an asymmetric cost matrix where false positives (FP=decide to invest but need to write it off later) are OK/less costly as they can lose their money only once, but where false negatives (FN=decide to not invest but turns out to be a multi-billion dollar company later) are NOT OK/more costly as they miss an opportunity to multiply their money several times.

Obviously, VCs could decrease FN by investing in every company but in reality, they face natural limitations such as a) how many companies a human VC can look into more detail for screening and b) how many companies a VC can invest in given a fixed fund size, clear split of initial versus follow-on allocation and approximate target with respect to the number of companies in mind. Therefore, a successful VC needs to improve recall (=reduce false negatives) with a fixed number of investments as a limitation.

Confusion matrix as a prerequisite to calculating Recall

Cutting through the noise

How can VCs improve recall while being sensitive to capital constraints? Having spoken to more than 150+ VC firms about their screening processes (partially throughout the course of my PhD research, partially thereafter; detailed overview in my paper here pg11-14), I identified two important screening dimensions and four major groups of screening approaches.

The two most important screening dimensions are:

Subscribe to DDVC to read the rest.

Join the Data Driven VC community to get access to this post and other exclusive subscriber-only content.

Join the CommunityA subscription gets you:

- 1 paid weekly newsletter

- Access our archive of 300+ articles

- Annual ticket for the virtual DDVC Summit

- Exclusive DDVC Slack group

- Discounts to productivity tools

- Database Benchmarking Report

- Virtual & physical meetups

- Masterclasses & videos

- Access to AI Copilots